Recent Articles

Popular Makes

Body Types

Ford F-150 Aluminum Body Review

2017 Ford Super Duty Aluminum Body ・ Photo by Ford

Five years from now the world will know if Ford‘s decision to use aluminum instead of steel for the passenger cabin and cargo bed of its all-new F-150 pickup was a brilliant move or an expensive blunder. Time will tell us if operating and repair costs for the alloy-clad full-size pickup drove consumers away in droves – and cost the automaker ownership of the “world’s best-selling vehicle” title – or if the fuel-efficient and corrosion-resistant truck transformed the segment and further solidified its strong sales lead.

When details of the redesigned F-150 were announced in January 2014, the use of aluminum drew immediate praise — and plenty of criticism. Advocates pointed to such benefits as weight savings and fuel economy, but detractors said the unusual material would increase purchase and insurance costs, and even minor fender-benders would be far too expensive to repair for the average truck buyer.

Is Aluminum New to the Automotive Industry?

Consumers are familiar with aluminum as a durable, recyclable beverage container and as the primary building material of commercial jet aircraft. In both of those cases, and thousands more like them, aluminum alloy is selected, because, compared to steel, it is lighter and more corrosion resistant, malleable and elastic.

Automakers first embraced the alloy more than a century ago: The first car with an aluminum body was shown at the Berlin Motor Show in 1899, and two years later Karl Benz introduced a new race engine with innovative aluminum parts. In more modern times, Acura introduced its groundbreaking all-aluminum NSX sports car in 1990, and Audi debuted its aluminum A8 sedan just four years later, removing more than 500 pounds of mass from its flagship sedan. Land Rover, Jaguar, and Aston Martin soon followed those leads, introducing their own aluminum vehicles. (It is important to note that no aluminum cars have reverted to steel construction.) F

ord is no stranger to aluminum, either. In 1993, the automaker introduced the Mercury Sable AIV (Aluminum Intensive Vehicle) program, which built about 20 sedans with all-aluminum bodies. In 2002, it introduced the GT40 Concept car, which would go into production as the all-aluminum Ford GT supercar several years later (its successor, the 2017 Ford GT, debuted at the North American International Auto Show in January of this year).

Today, aluminum is used across the industry in automotive powerplants, suspensions, subframes, body panels and interior components. In 2015, nearly every automaker is offering at least one vehicle in its lineup with lightweight aluminum body panels, whether hood, trunk lid, roof or tailgate.

Why an Aluminum Full-size Pickup?

Steel, the traditional construction material for trucks, is strong, inexpensive, readily available and easy to repair. It is also, however, heavy and prone to corrosion – compelling reasons the automotive industry is moving toward alternative materials.

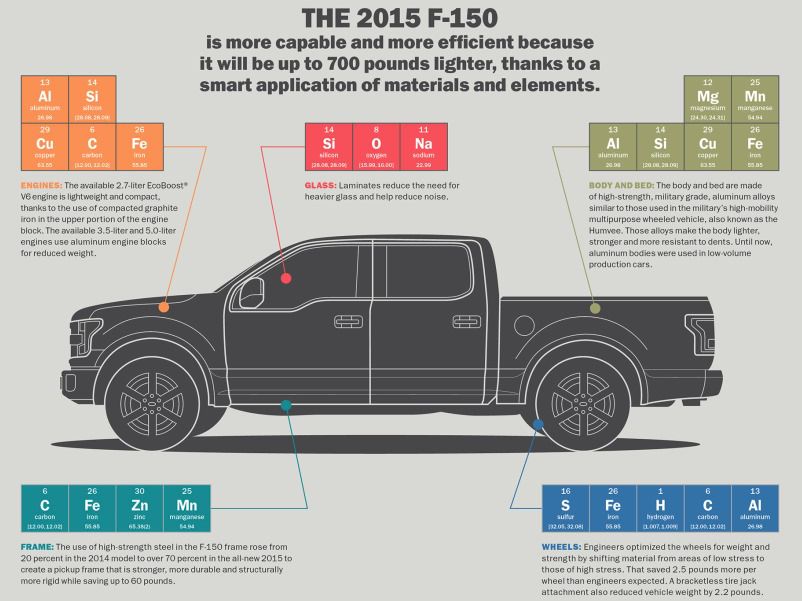

Ford engineered its F-150 to be constructed with an aluminum alloy cab and bed (the frame is high-strength steel) to take advantage of aluminum’s durability and weight savings. In addition to being highly resistant to corrosion, the use of aluminum saves upwards of 700 pounds of mass per truck, which Ford says delivers the following benefits:

- Increased fuel economy

- Increased capability

- Improved performance

Increased Fuel Economy

Compared to the previous F-150, the new model earns up to 29 percent better fuel economy. The new numbers are impressive, but reduced mass isn’t the only factor improving efficiency — the trucks are aerodynamically sleeker, and the engines have been refined.

Shedding weight offers another benefit. With fewer pounds to carry, a smaller engine could be used. This explains the arrival of the new EcoBoost 2.7-liter turbocharged V6 engine. With 325 horsepower and 375 pound-feet of torque, it offers the functional equivalent of rivals’ small V8s, but it delivers better fuel economy and weighs about 40 pounds less than Ford’s traditional 5.0-liter V8. T

he fresh 2.7-liter is the fuel economy leader with EPA mpg ratings of 19 city/26 highway with rear-wheel drive (18 city/23 highway with four-wheel drive). While that doesn’t match the economy of the 3.0-liter turbocharged diesel in the RAM 1500 — that wasn’t its objective — it does make the 2.7-liter the most fuel-efficient gasoline engine in a full-size pickup. The new 3.5-liter V6 base engine is fairly efficient, too, with EPA ratings of 18/25 with rear drive versus 17/23 for last year’s 3.7-liter V6, a five-percent improvement.

The F-150’s other engines reveal similar gains. The 5.0-liter V8 in the 2015 model is rated at 15/22 with rear-drive and 15/21 with 4WD; in 2014 it was, respectively, 15/21 and 14/19, a six-percent increase. The new 3.5-liter EcoBoost V6 comes in at 17/24 with rear drive and 17/23 with 4WD versus 16/22 and 15/21 from last year, around an 11-percent increase.

Increased Capability

A second advantage is increased capability. The math here is pretty simple. With less of its own weight to carry around, the F-150 is capable of hauling a greater load. Ford attributes these gains directly to the F-150’s weight loss: Maximum towing increases from 11,300 to 12,200 pounds; max payload jumps from 3,120 to 3,300 pounds.

Photo by Ford Media

Improved Performance

Again, simple math at play: With less mass to move, the engines can move the truck faster, and the brakes can slow it down more quickly. Recorded acceleration and braking figures back that up: Car and Driver magazine tested a 2014 F-150 4×4 with the 3.5-liter EcoBoost V6, and it sprinted from 0 to 60 mph in 6.4 seconds – the 2015 model obliterated that time with an impressive 5.6-second run. Tested braking distances showed a similar improvement: The 2014 truck came to a halt from 70 mph in 186 feet, while the 2015 model took only 179 feet. The reduced weight also aids handling, contributing to improved road manners.

What Cost, Aluminum?

The advantages might be apparent, but what about the costs? Ford reportedly invested more than $3 billion into its plants to accommodate aluminum vehicles, and the raw material costs about twice as much per pound as steel – surely some of that will be passed on to the consumer. Our research indicates that some of those costs have indeed been passed along, but not much.

Ford has been able to keep the price increase reasonable for a few reasons:

- Even though aluminum is more expensive than steel, Ford is able to recycle the aluminum scraps far more effectively than it can steel, and those scraps are worth considerably more.

- Pickup truck prices have risen sharply in recent years, so there is more room to absorb the extra costs.

- Ford sells more high-profit high-end models than ever before, which further pads the profit margin (it is now possible to option an F-150 to beyond $60,000 – this would have been unheard of a decade ago).

The F-150 does cost a bit more than the outgoing truck, but not by much — overall, the price increase is about $395, model for model.

Are Insurance Rates Affected?

Some argue that the sticker price isn’t the only cost to consider when buying an aluminum vehicle. They point to additional insurance costs, heightened repair costs, and the scarcity of shops capable of working with the alloy. (Ford told us that insurance rates represent only about 11 percent of the average cost of ownership for F-150 customers, while fuel and depreciation costs represent about 68 percent of ownership costs — it expects the cost of ownership for the all-new F-150 to remain similar to or less than today’s levels.)

Insurance rates rely on the history of a vehicle. This means the costs to insure the 2015 F-150 are based on 2014 F-150s, not the current model. Insurance companies are loathe to give out information on insurance rate percentage increases, citing the data as proprietary. However, they will give quotes to prospective customers — so we picked up the phone.

We secured quotes from Progressive Insurance on an F-150 V8 with extended cab, Chevrolet Silverado 1500, and RAM 1500. The Chevy was the least costly at $351 for six months of coverage. The F-150 ran just $2 more at $353, and the Ram was the most expensive at $376. State Farm Insurance has also gone on record that its rates for the all-new 2015 Ford F-150 are in line with those of the 2014 Ford F-150. For now at least, our quick survey shows that the aluminum in the F-150 isn’t having an adverse effect on insurance rates.

However, that may change. Those rates could go up in the next year or so as more F-150s get into accidents and reveal the true cost of repairs. A study released in April 2014 by the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) concluded that aluminum-bodied vehicles have higher collision claim severities (costs) than steel-bodied vehicles, and the more aluminum used in a vehicle, the greater the increase.

The F-150 isn’t the first aluminum-bodied vehicle in the United States. As mentioned, the Audi A8 has had an aluminum body since the mid 1990s. Data from the HLDI study shows that, from 1997 to 2013, the A8 had 14-percent higher overall claim severities compared with its steel chassis counterparts — the BMW 7 Series and Mercedes-Benz S-Class — and the odds of an accident resulting in a total loss were 1.12 times higher.

Another HLDI analysis included vehicles with low, medium and high percentages of aluminum content. The results revealed that vehicles with high aluminum content, like the A8 and Jaguar XJ, had claim severities 20-percent higher than those with low aluminum content (such as older versions of the Audi A6, Jaguar XJ, and Mercedes-Benz E-Class), and a nine-percent higher claim severity than those with medium aluminum content (such as newer versions of the Mercedes E- and S-Class and BMW 5 and 7 Series).

Are Repair Shops Easy to Find?

As part of the F-150 rollout, Ford exceeded its goal of training at least one aluminum technician for 1,500 shops — roughly 750 dealers and 750 independent shops. Ford has some 3,100 dealers, but only a fraction do collision repair, so these numbers indicate that Ford has trained much of its dealer network to repair aluminum. And, unlike other automakers who restrict sales of specialized aluminum components to only select dealers, the automaker will sell its Ford Genuine OEM collision repair parts to all dealers and body shops. (Note: Not all Ford dealers have aluminum-qualified body shops. Owners need to use Ford’s Locator Tool to find the proper shops in their local area.)

On the other hand, 750 out of the estimated 35,000 independent shops form quite a small percentage. Ford says, though, that 90 percent of customers will be within two hours of a shop that can fix the aluminum-bodiedF-150, the same standard Ford had for the 2014 model.

Photo by Ford

Is Aluminum Difficult to Repair?

There are some notable differences between repairing aluminum or steel. First, the shop must have an area dedicated to aluminum repair, because steel particles can’t mix with aluminum or they will cause galvanic corrosion. Second, a shop needs tools dedicated to repairing aluminum for the same reason: If the particles mix, it can cause problems. And third, aluminum isn’t as easy to weld as steel. Considering the special tooling, training and shop investment required to work with the material, repairing aluminum is currently more expensive than repairing steel — as it is with any advanced material.

While the cost to repair aluminum vehicles is higher, the HLDI study notes that a high-selling, mass-market vehicle like the F-150 may change the dynamics of the aluminum auto repair market. As more shops are equipped to work with aluminum, and they begin to compete against each other, costs will go down.

Photo by Ford

Are Aluminum Parts More Expensive?

Ford purposely engineered its aluminum F-150 with modular components designed to be replaced quickly, as a unit, when damaged rather than hammered-out and laboriously repaired. Examples include the apron tube, which can be repaired without removing the dash; the floor pan and rocker panels, which can be sectioned to avoid requiring complete replacement; and the B-pillars, which can be repaired without involving the roof.

Ford shared parts prices with Autobytel, revealing that many of the aluminum parts, including all four fenders, have the same replacement costs as the steel parts from last year. The automaker has held its pricing on parts, but shops are expected to charge more to work with the alloy — as always, we suggest getting multiple quotes and hiring a certified shop.