Recent Articles

Popular Makes

Body Types

What is Adaptive Cruise Control?

adaptive-cruise-control-audi ・ Photo by Audi Media Services

The exponential growth of adaptive cruise control in today’s automobiles — not only on expensive luxury liners but on cheaper cars as well — means we all need to learn and understand the capabilities of this electronic nanny.

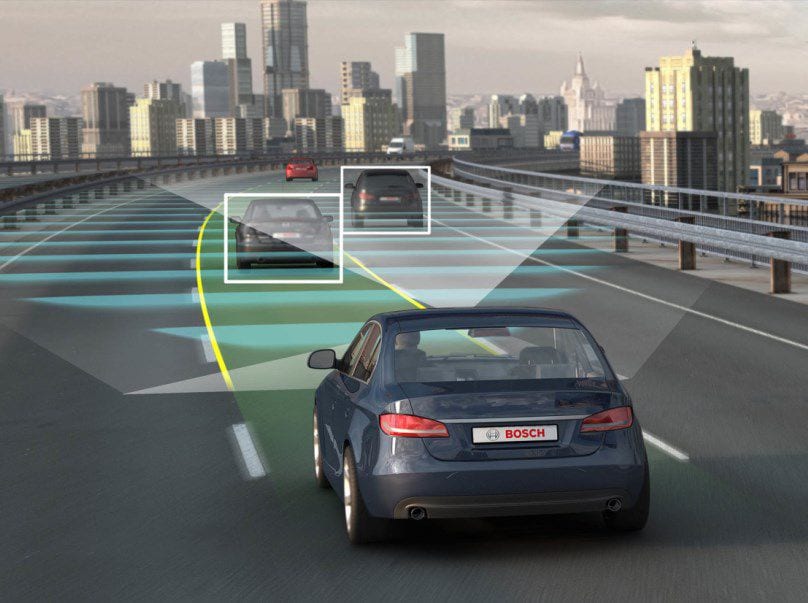

Adaptive, or active, cruise control (ACC) is an evolution of the speed-holding electronics that long-distance highway drivers have loved for decades. But unlike traditional cruise control, which simply manipulates the accelerator to maintain a set speed, adaptive systems have the capability to manage the gas pedal and brakes, measuring the speed of traffic, and maintaining a predetermined gap between other cars in the lane. Full-range ACC is able, like conventional cruise control, to accelerate to a set speed, but it also can decelerate to a full stop if vehicles ahead come to a halt. The cream of the crop can accelerate, stop, and then resume speed without any driver intervention if traffic ahead moves within a few seconds, such as in stop-and-go freeway traffic.

Set Desired Speed

From a driver’s perspective, ACC operates in much the same way as normal speed control — via controls located on the steering wheel or a steering column stalk. Once the system is activated, the driver “sets” a desired speed and can then toggle to a preferred following distance, or gap, between his or her car and the vehicle ahead. Shorter gaps reduce the spacing and likelihood of other cars cutting into your lane, but this can mean delayed reaction to slowing or stopped traffic. Some manufacturers permit the standard speed control to operate independently from ACC, allowing the driver to choose whether to engage the full-range system or simply use steady-state speed control.

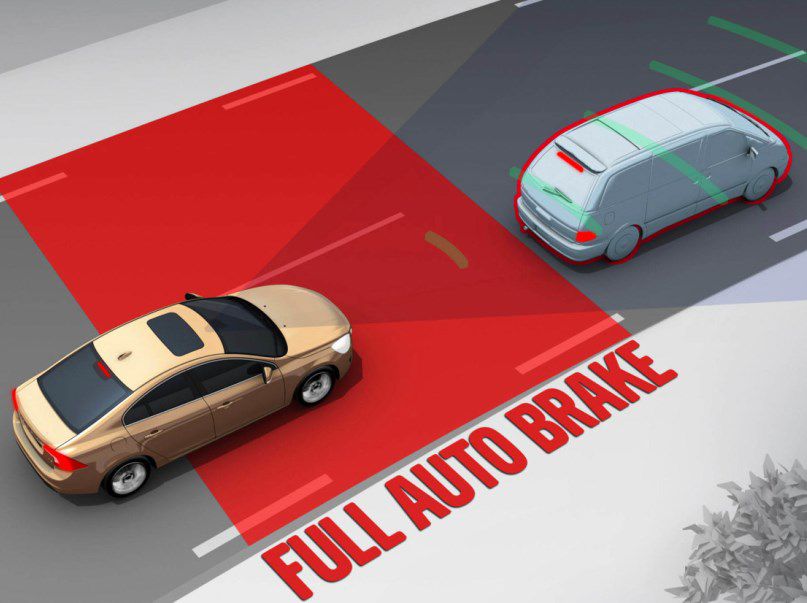

Forward Collision Warning

Safety is one of the main reasons behind ACC, and more automakers are adding forward collision warning to alert drivers of an impending crash. The more complex setups not only warn of an obstacle but also automatically apply brakes to prevent or mitigate the effects of a crash. Forward collision warning and automatic braking are not yet required by law, but America’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) recommends them and is considering making the systems mandatory. And the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) has already started to rank vehicles based on whether they offer collision warning and/or automatic emergency braking and how well those systems function.

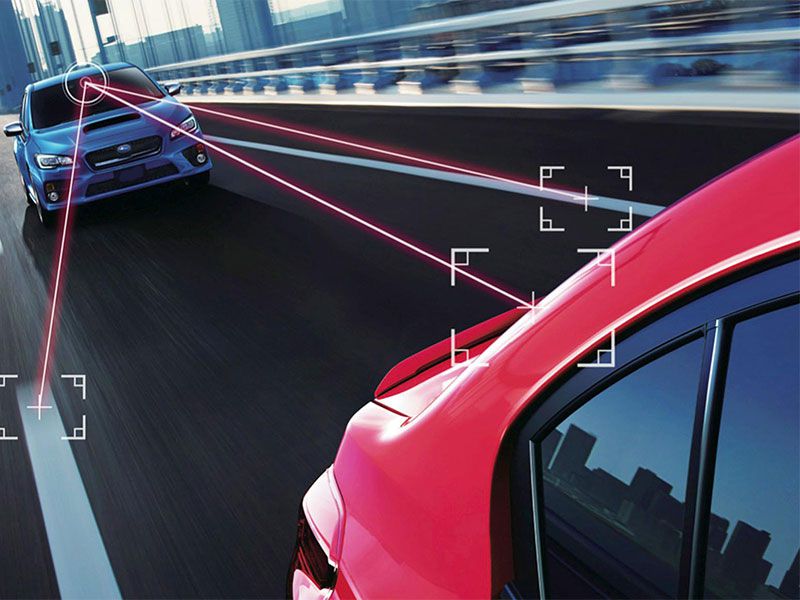

Radar

Radar is the essential element of ACC, accompanied by lasers and cameras, depending on the manufacturer. Most systems rely on the same Doppler radar that allows air-traffic controllers to safely manage thousands of flights and helps weathercasters read the speed and intensity of storm patterns. To work properly, sensors for automatic braking must accurately and consistently detect obstacles, while screening out false signals from common items such as metallic highway signs above or adjacent to the roadway, poles, trees and other vegetation, and even inaccurate reflections from the road surface. To do this, radar beams must be tightly focused, typically emitting a 40-degree V-shaped pattern running out to as much as two-and-half football fields (250 yards) in front of the car. The radar signal needs to reflect off vehicles on the road without picking up other obstructions and “see” far enough ahead to allow the vehicle to react in time to slow down. The echoes must be quickly and carefully interpreted by onboard computers to avoid overreacting to roadside obstructions on curves.

Basic ACC uses simple radar sensors, sending out a narrow, long beam and using the echo to calculate distance and relative speed. Because of a lack of short-range sensing, these systems tend to function only above a certain speed, typically in the mid-20-mph range, and are intended primarily for use on the open road. For those of us who often test vehicles with a system, having the ACC flash a warning and maybe a beep, and then shut down while braking to a stop, can be unnerving. Owners would no doubt get used to this type of control.

Photo by Subaru

Advanced ACC

Advanced ACC systems typically found in luxury brands employ dual coverage radar signals: A tight, long-range beam is used for highway work, while wider short- to midrange beams detect nearby vehicles cutting into the travel lane and help with stop-and-go traffic. Subaru’s system, called Eyesight, uses stereoscopic cameras to judge depth and distance much like the human eye. Some systems can even distinguish pedestrians or animals from vehicles. The best systems today bounce radar signals under the car ahead to detect the action of the second car ahead, giving onboard computers information about traffic flow that even the driver sometimes cannot perceive. Some ACC setups will automatically restart from a stop or will hold the brake and restart once the driver taps the “Resume” button or touches the accelerator. Others completely disengage at a stop, releasing the brake and handing over all control to the driver.

Many drivers don’t like the idea of permitting their vehicle to take care of accelerating and braking. But I’ve found that systems like Mercedes-Benz’ Distronic Plus have the potential to take all the drudgery out of commuting, at the same time allowing me to take back full control when the open road beckons. I’ve used Distronic Plus and similar systems to handle everything from 70-mph cruising all the way down to a full stop in stop-and-go congestion and back up to 70 mph, all without my feet ever touching the pedals. Good systems today also provide a visual indication — usually a car-like icon — to show when the sensors have detected a car in the path ahead.

Autonomous Driving

Are these systems completely foolproof? I’ve encountered a number of irregularities, including some systems failing to detect other cars in the road, especially when those vehicles are at a full stop, so at this point, it’s clear that driver attention is still a major component.

What’s next? ACC is a giant step on the path to highly autonomous driving, which automakers predict will be available by 2020; fully autonomous vehicles will follow. From our perspective, having driven nearly every type of ACC-equipped car on the planet, there’s clearly a need for common standards so that, like antilock brakes or airbags, ACC functions in the same, predictable manner across all vehicle brands.